|

10/6/2017 Wet Sand ChorusSALT SEAS THAT LIVE INSIDE ME - JANE-REBECCA CANNARELLA I wear sand on my skin like it’s body paint. My entire life has been a combination of salt water, and seas that live inside me, and the kind of beachfronts that home little pebbles in lieu of soft sand. When, as a child, I moved to San Diego, CA and discovered beaches made from silk sand and pink rocks I would sleep on the silt—my body damp with the spray of the waters. Rising from my nap, I would be covered with a layer of grain. A prehistoric exoskeleton that coated the shape of a pre-teen. The sands have always existed within me and outside me. How many trinkets from my childhood live in the gritty earth—East Coast / West Coast? Barbie dolls I buried too deep. Cried about on the way home. Rocks from the shores of the Long Island Sound marked their anonymous graves. They live in the sand-soil now, the gentle lapping of the Shore their beachfront in perpetuity. And then there were the rings that fell from my fingers slick with the water, lightly dancing their way to the ocean’s floor. And a best friend’s necklace that slipped off my neck while doing cartwheels, the mounds of sand cushioning my fall. These fragments of me all live in the sand. They’re a part of grave of granular erosion that now exists independently of my body, making the beach their forever home. But when I lay on the fine particles, the seeds of the ocean polishing themselves into my skin, I feel eternal. The sand is a fleece that centers me. I’m connected to the ocean, and the earth, and the segments of myself that I’ve lost or left behind. SOMETIMES, NEW JERSEY - CASSANDRA PANEKIn high summer, on a precious day off, my friends want to go to the nude beach. The weather is perfect, someone left a sun hat in my trunk, and I’m ready to relax. Fast forward to me, stark naked, feet blistered from burning sand, chasing our rainbow umbrella parallel to the ocean, praying it doesn’t strike a nudist. I don’t love being naked. I don’t love running. I don’t love running naked. The beach is horrible, insubstantial, littered with sharp shells, and the umbrella—a rainbow cocktail garnish with delusions of olympic javelin grandeur—is faster than I am. The wind coughs and dies. I return victorious to our blanket, face flaming with exertion and fresh sunburn. My friends are angels and don’t laugh. Seeing me struggle to plant the stubborn thing again, a heavyset man adjacent to our plot takes pity, folds his paperback shut, and offers help. “The trick,” he tells us, “is to take the sleeve the umbrella came in, and tie one end to the spokes and the other to your heaviest bag.” Then he wishes us a pleasant day and returns to his book. Unlike our umbrella, unlike the loose sand creeping and blowing everywhere, unlike the drifting naked opportunists with greedy eyes, this man is steady, permanent. Crisis averted, I cool my heels in the sea. The sand is nicer here, wet and malleable between my toes, soothing my scorched skin. I wriggle into it like a crab, and bury myself to the shoulders in the grey ocean. My girlfriends laugh from the shore as a man flips wet hair behind his shoulder and tries to flirt. Cloaked in the ocean and rooted in seafloor I don’t feel as vulnerable as I did on land. I make polite until he leaves with an attempt at a showy dive that flashes his ass in my direction and splashes me in the face with salt water. My friends are angels, but they’re laughing now.

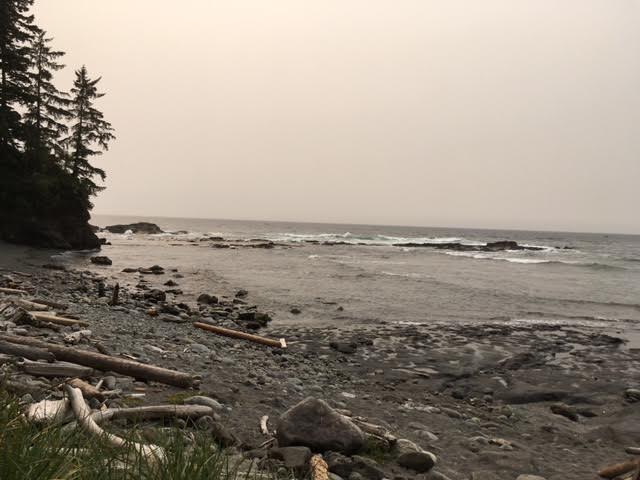

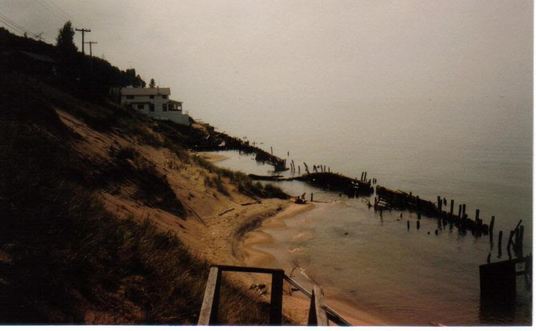

A PHOTO BY A BED - SAM WILLIAMSIn my late mother's bedroom, for pretty much the entirety of my childhood, stood a picture on her bedside table. The picture is of—in this order from left to right—my grandfather, my sister, me, my dad. I'm just barely three-years- old. My sister is six. My dad is in his late thirties, my grandpa is in his early sixties. We are all holding hands, standing on a beach in North Carolina, looking out at the water. The picture is of our backs. This is one of my earliest memories, if not my earliest memory. We stood there because I requested to. I wanted to stand in the water and let the waves bury my feet in the wet sand. This was my favorite thing to do in the entire world. As a small child, my excitement level would skyrocket when told we were going to go to the beach. The only thing I wanted to do when we first got there was stand in the waves. My mother took that photo. She loved it so much she kept it right by her head as she slept. I wonder how many times she looked at it right before closing her eyes to sleep. Walking into my childhood home, located in Bow, New Hampshire, one thing became apparent. There were no pictures of my mother. She hated being photographed. A rather large woman, I believe she couldn't stand the way she looked in most photos. My sister eventually took a photo of my mom that she liked. A copy of that resides on my bedside table. There were lots of photos in the house. My dad's office had photos of the family. My mom's office had photos of the family. I had photos in my bedroom. So did my sister. But not one of my mom. Yet, no photo ever held the esteemed place that this photo, the four of us standing in wet sand, had. My family has taken many beach vacations together since, but we never snapped another photo like that. We never stood together, holding hands, letting the ebb and flow of the waves sink us into a trap of sand. Yet, every time I'm at the beach, I take a few moments to let the water run over my feet, and I think of that photo, and I think of my mom. VANCOUVER ISLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA - LEVI ROGERSThe sand on Vancouver Island is slate grey and coarse, a delicate bluish black. While the island contains oceans and beaches, they are not what one typically thinks of when one hears the words “ocean,” “beach,” and “island.” This is the Pacific Northwest. The Sitka Spruces and Douglas Firs stretch tall, slender, and heavenward from the middle of the island. The reflection off the black of the ocean seems to be shading the trees a dark, seaweed green. The water is clearer here. The brush thicker. The roads made of dirt and void of signs or vehicles. Black bears and black berries roam wild through the forest, practically nuisances and weeds instead of the beautiful rarity I am used to thinking of them as. Smoke from fires in British Columbia, Montana, Idaho, and Oregon currently smother the island in an apocalyptic haze. My family and I are here for a mini vacation after my brother’s wedding in Seattle. My parents, my sister, and my brother-in- law. Yesterday we walked a mile down through the ferns and spruces to Botanical Beach—the last stop for many backpackers completing the Juan De Fuca trail that starts some 40 km south. The tide pools were empty as we stared out over the Pacific Ocean, nothing between us and Japan but water and ocean life. What is it about the smell of salt and seawater that always makes one want fish and chips? I have always been drawn to the geography and landscape of the Rocky Mountain and Pacific Northwest. The granite, the pine, the elk, the moose, the snow, the rain, the trees. Perhaps it’s in my blood from growing up in Colorado. Up here though, in Canada, on the Western side of the island, my brown boots marauding through the wet sand and lichen, I am reminded of a time when everything was more plentiful—salmon, halibut, bears, cougars, trees. Everything was more plentiful, of course, except for white Europeans—who brought smallpox as prolific as blackberries. In the tourist shop, I buy a bottle of Brambleberry jam and a microfiber dishtowel with a totem pole. Am I continuing a legacy of use and cultural appropriation? On our last day, we board a ferry to Vancouver the City, from Vancouver the Island. There is so much I don’t know about the world. For instance, “How do ferry’s float?” The idea that ferries can shuffle a hundred passengers and cars across water on a layer of steel seems more fucking impressive to me than airplanes or iPhones. My friend Alex tells me this is called displacement. “As long as the area displacing water weighs less than the water that would occupy that space, a thing will float.” As we leave the town of Nanaimo, the ferry’s horn sounds. My mom, wearing a blue fleece, screams and covers her ears like Laura Palmer. One day I’ll spew all my desperation out in an orderly fashion. Hire some friendly employees of the BC Ferries to help me get the words out of my mouth, float them across the bay. They’ll motion silently with their orange wands and yellow reflective vests: “You this way. You this way. Row number one, seven, thirteen, etc.” Everything in its right place. in june, at the beach up the street - CAESAR KENTIn June, at the beach up the street, I interrupted myself mid-sentence to kiss her. My hand had been twitching for hours, restless, the way a beach is, reconsidering the polish of wet sand, regardless of footprints or driftwood. In August, Vanilla Bean told me her hand had been waiting for mine. By September, she had a shelf in the shower for her nectarine body wash and a drawer in my bathroom where mellowing fragments of last week's uterine lining jostled my nose from the trashcan I held under my chin as Vanilla Bean combed the side of my face with my electric razor. She said her ex, the one who became someone else, never let her shave his face. I told her it grows back. I sat on a towel on the toilet lid while Vanilla Bean leaned over me, stabilizing herself with a hand on my forehead. There was a noise outside the window, left open to release the steam from our shower; she didn't look, and I could only see darkness beyond the screen. It was the neighbor across the fence, or the wind, or a possum—and if it were some benign voyeur, watching the absent-minded draw of my hands to Vanilla Bean's nipples, her habitual slapping like waves lapping the shore, all the better not to know at all. I taught her the grain of my skin, guided her around the dune of my throat. "Where's the Barbasol?" Vanilla Bean asked once she'd buzzed all but my chin and upper lip, our faces and shoulders littered with the flotsam of beard and sideburns. I pointed to the shaving cream from the hippie market on the other side of the island and she cradled it in her hands. It's unscented." She squirted some into my palm. "I like the way Barbasol smells. My dad uses it." I lathered my face for her, and she took to the stubble along my jawline with the razor head in timid strokes. "You're going to cut me that way, love," I told her. I took the razor from her hand and showed her how to press the blades against the skin, cascade the razor through the foam, leave smoothness in its wake, placed it back in her hand. Vanilla Bean carefully glided the blades across my cheeks and neck, and she didn't have to say that this was her way of returning the favor of shaving her calves since her back procedure, and I didn't mention that my grandmother had done nothing and told no one about the cancer for a year, and when she was done, Vanilla Bean cleaned me with the soggy corner of a towel and ran her fingers along where hair and stubble once had been. We stood in the mirror, my chest to her shoulders, my arm slung around her neck, looking into each other's eyes through the reflection, almost posing, clean and soft and new, together. TWENTY-THREE YEARS AFTER LAKE MICHIGAN - MARIE MARANDOLAMom stood thigh-high in the lolling lake. (My floating ribs. Joey’s middle chest.) She stooped and scooped at a sub-surface shimmer. A pair of minnows arose in the cup of her hands. The school swam on. I remember those minnow summers, lying on my stomach on a red plastic raft, eyes and one hand drifting, the uncovered circle of my back painted by coat after coat of afternoon sun. Then later, finger-digging in the shore for rocks and shells; saving orange butterflies from the swells, taking them up the beach to air-dry their wings. Mom, our own wilderness camp counselor, showing us the chipmunk paused on the porch rail, the symmetrical seedpods that twirled when they fell, and tiny fish. She held the minnows out to us, invited us to gently stroke their rainbow spines. And I did. And Joey said (the story goes), “Mom? I’m not the kind of kid who likes to touch fish and bugs and dirt.” Twenty-three years later, I stand barefoot on my patio, watching my dog kick at grass in the yard. I stand and I watch, afraid of little clinging things hiding in joints of the metal-backed chairs. I hold my breath walking past the broken husk of a hornets’ nest, empty in the driveway for days. I pull the screen tight against the silvery moths that surround the porch light-- I catch myself. I think of Joey, his low, little-boy voice, saying his piece. “I’m not the kind of kid who...” And the girl in the lake, in the sand. Did my brother’s leaving leave his position open, leave me squeamish, leave me sensitive? Have I inherited his ghost? Up on the street, the wind has shaken loose the seeds of things. I get closer to the trees than I have in years, crouch and pick up a small green acorn. Then another. Until I have a fistful I don’t want to lose. The hard points of the shells press into my palm as I head towards home. WET SAND: AN INAUGURAL SCENE - ALEX SIMANDYou are three years old. You cling to your father’s neck, slick with sweat and oil, the burgeoning of gray hairs on his back your first introduction to aging. His skin folds as he looks up, then forward. He is holding your legs, chicken winged in the crooks of his elbows. He lowers himself—and you with him—into cold Caspian waters. Waves roll in, the sea panting like a Caucasian Shepherd, beating over and over, your father your shield, but you feel him shudder from the strain of wading. You feel the violence of nature through his chest and in your arms but you are safe. He is taking the brunt of these liquid daggers. You feel protected. You cannot say why, but you release your father’s neck just as a wave—five meters, ten meters, twenty meters tall—rolls in black and looming, smelling of fish and other dead matter. Your father lets himself lose his grip on your legs and you are tumbling, rag-doll perfect fist over foot over seaweed over Sturgeon over mustache. The brine bellows frothy and white then mutes itself dark again. You think you see your mother’s face somewhere, craning her neck, your father ducking the waves, swimming away from you. Pebbles invade your eye sockets and run over the flat part of your skull. A million years of revolution on your tongue. You tumble. You are still tumbling. You never stopped. You cannot ever stop. You never made it out alive. SAND - ERIC ZRINSKYSam is never quiet. Sam is calamity. Sam is talking loudly in public about venereal diseases she does not have. Sam sneaks embarrassing personal hygiene products into the cart for my mother to discover in horror at checkout. Some nights we steal realty signs and re-appropriate them in front of homes that are not for sale. Always a plan. Never a reason. Sam, forever smoking clove cigarettes like a goddamn art-school stereotype. I love her. I hate her. All jeans, all black band t-shirts and studded belts. *** The sand laps at the receding water. Clear sky filled with stars—the kind of view lost to city-light most nights now. Breeze-chilled late October cool. “I love it here,” she says. This is Sam's "perfect" place. Cold and calm. Solitude. This is where she gathers all of the quiet in the air, fills her lungs, and holds it like a child squeezing a stuffed animal to her chest. Her body slacks and she exhales. I watch her breath dissipate into white vapor. The ducks call each to each across the pond. The drip, drip, drip of Sam's piece-of-shit Pontiac on the gravel road. We'll fill the infinitely leaking coolant again before we leave. I don't respond. *** I am in front of her casket now. Face up with eyes sewn shut and cheeks swollen with permanent sleep and formaldehyde-filled veins. The skin is plastic. This is Samantha, but it's not Sam. Her father stands near her body and recognizes me as I approach. It’s been years, but I embrace him with both arms. I don’t let go. I cry, openly, loudly. I carry on like a child. This is her scene. This is how she would have done it. On the way out of the funeral home, I steal all of the prayer cards because I can't stand the thought of anyone else taking a piece of her with them. *** I used to get emails from her family about benefits and charities in her honor. I did not respond. They do not write anymore. *** Eleven years dead, I write a poem she will never read and I hold her ghost like sand holds water. we were untouchable

until one of us broke. scraped knees and ripped jeans running through the woods and streaking like children and we were unshakable, until one of us gave in. and I read the note over and over-- chewing on the words, trying to make sense of blurry syllables-- and we were all so young, until we grew up. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorOur fabulous blog team Archives

June 2024

CategoriesAll 12 Songs Art Art And Athletes Book Review Chorus Blog Date This Book Game Of Narratives Guest Blog Letter From The Editor Lifehacks Movies Of 2019 Music Pup Sounds Smackdown Strive For 55 Summer Playlists |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed