|

Sean Lynch is a writer and editor who has published five books of poetry, including his newest collection, Halo Nest: Poems on Grief. The book is a reflection on his journey with grief before, during, and after his mother's dying of cancer in 2017. When did you start writing the poems featured in this collection, and throughout how long of a time period? What is the first poem you completed in the collection and the most recent? Emotionally how do these poems compare to one another? Some of these poems, such as the poems about Ireland, were written long before my mom was even diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2016. I included them because I have long had a sort of obsession with death. I started writing poetry as a teenager in order to deal with existential angst. When I traveled to Ireland in 2013 and explored the rural western countryside, I felt this profound, bittersweet sadness at the beauty of the landscape and its desolation due to the legacy of an Gorta Mór. My mother was extremely proud of her Irish heritage, and taught me Irish songs and poetry growing up, so I had this connection between her and Ireland. There was an intergenerational conduit of grief that generated my interest in poetry and led me to write poems in order to deal with my mother's death.

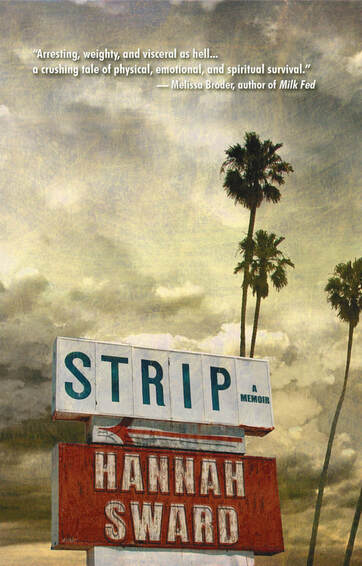

That being said, these poems span about a decade of writing, rewriting, and editing. It's hard to tell which poem was the first completed because I spent years going back to them and making both major and minor changes to them. "Of Famine Roads" was probably the earliest started as it was based off of notes I took while I was in Ireland and inspired by the poem "The Famine Road" by Eavan Boland. The last one I completed was "South Philly Casualty," which is about the murder of my great grandmother in 1980 and inspired by the Seamus Heaney poem about the Troubles called "Casualty." Upon first glance, if you didn’t know that memoirist Hannah Sward—author of Strip—and I are both Jewish women who graduated from Antioch University Los Angeles, you might not think we have much in common. She is a recovering addict (meth and alcohol) and former sex worker who suffered early childhood sexual abuse—three boxes I cannot tick. But isn’t the human condition so much more nuanced than that? When I read, “I waited for this terrible [yearning] in me to go away…an aching that I didn’t like, a longing to find comfort in another,” I thought—yes. I felt seen. I kept turning the pages late into the night, my bedside lamp a source of light through some dark moments in Sward’s layered life. “The saddest girl in the world,” Sward is abandoned by her mother in her youngest years and finds herself wondering “what kind of woman I would be like if my mom hadn’t left.” Her poet dad meanwhile, though a mentor to her, is also busy with his pursuits—from typing all the “poems in his head” to spirituality to women who are not Sward’s mother. While my own parents didn’t leave physically, both were unavailable in their own ways, so I was familiar with that deep sense of childhood loneliness (for which I was put on anti-depressants at age ten), and, later, with a desperate neediness for which I too sought counseling at the same Beverly Hills, sliding scale center as Sward did. Fortunately, I never got into drugs (my father was a habitual pot user, and I very much resented the foggy haze that separated him from us, even when he was around), but I certainly had my vices. Though I never made a career of it, I—like Sward and her mother before her—was promiscuous and probably could have benefited from a 12-step program for addictive tendencies of my own, love among them. So, when I say that I kept seeing myself on the page, I don’t just mean on the surface level, even if Sward and I do share a similar hair color and Canadian roots. I mean that, in baring more than just her skin, Sward taps into the universality of what it means to be human, and this is what kept me invested in her story. “I was unhappy. I didn’t know what I was doing with my life…I loved the ritual,” she writes of her descent into meth use. I made a checkmark in the margins. I could have written the same sentences about myself, only my ritual of choice was getting ready for dates. Those dates, and the two drinks I usually ordered on them, helped to take the edge off—the edge being how alone I was in the world, an edge Sward and I (and so many of us) share. “Maybe I would have…made choices that weren’t destructive, if I had formed a [healthier] sense of self,” Sward muses, and I often thought the same as I found myself in an endless loop of date-going—countless, interchangeable dates on which I almost always had casual and unprotected sex—until eight years ago, entirely by chance, I met my future-husband on one of them. As my grandpa says, life is a series of accidents. In my case, ninety-three sexual partners in, I accidentally met someone (my 94th) who loved me in spite of the childhood wounds that shaped me into the needy woman holding onto her wineglass as tightly as I’d hold onto any man who’d let me. In Sward’s case, she accidentally got hooked on drugs—which she only planned to use temporarily to lose weight—and caught in a cycle of sex work—which she only planned to do in the short term to make cash for college. My path wasn’t so divergent from Sward’s, until it was. My series of accidents could have led me down a different (and much darker) path entirely—one that included sexual assault or sexually-transmitted infections, for starters—and I have only luck, not good decision-making, to thank for the fact that it didn’t. For Sward, there is luck, even if bad luck, and then there is the deliberate choice to get clean, which altogether alters her course for the better: I was thirty-six, lying on the floor of my pink bathroom on a Saturday night in Los Angeles, torn red from fighting with vines in the garden…I don’t like gardening…but on meth it was very interesting…I saw no escape…How many years had I spent in the bushes with my head down, tangled in the weeds…of my life? I told you as much in the first paragraph, so you already know that our heroine finds a way to untangle herself from addiction, and I’m so grateful that she does. But it’s not only sobriety that she works hard at. She also “face[s] the lonely, frightening” prospect “of sitting with [her]self…in the hours…with the words” to write this book—a fact for which I’m equally grateful. Before ultimately finding redemption, Sward—always with the loveliest, most lyrical language—shares her lowest moments, her secrets, and her very soul with us, so we readers can see our own imperfect, complicated, sometimes-ugly-but-more-often beautiful souls reflected right back. STRIP Tortoise Books, pp. 264, $17.99 Sept. 6, 2022 publication date ISBN: 978-1948954679)

|

AuthorOur fabulous blog team Archives

June 2024

CategoriesAll 12 Songs Art Art And Athletes Book Review Chorus Blog Date This Book Game Of Narratives Guest Blog Letter From The Editor Lifehacks Movies Of 2019 Music Pup Sounds Smackdown Strive For 55 Summer Playlists |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed